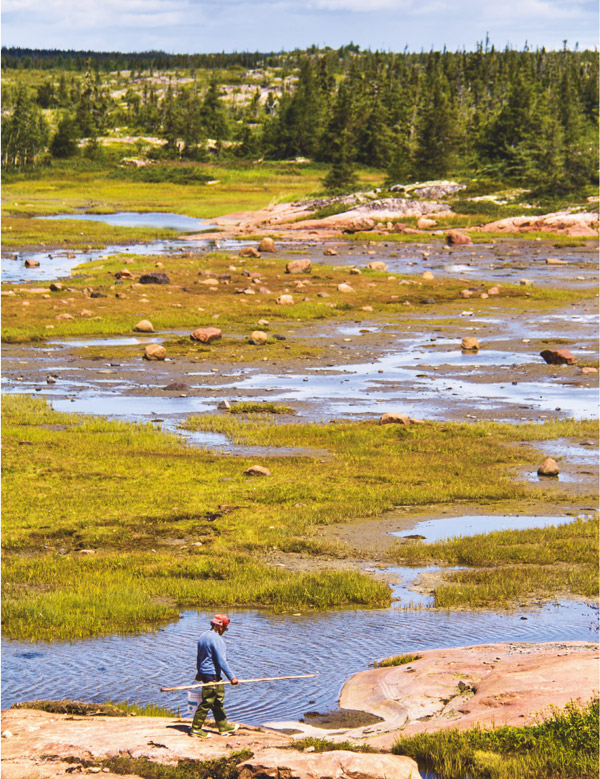

For a long time, the North Shore’s relative isolation made it hard to import fresh foods. Its Indigenous and European-descended inhabitants largely depended on locally accessible resources, including wild-harvested plants. Today, though grocery shelves are well stocked, many locals still head to the forest to forage for treasures.

BY LAURA SHINE

“I went up to Sept-Îles yesterday and I almost stopped along the way to greet a woman picking spring red berries. These berries spent the winter under the snow; they’re delicious and very sweet in the months of April and May.”

Guy Côté is a Havre-Saint-Pierre historian who writes about the culture and history of the North Shore. He tells a tale of the quasi-miraculous harvesting of these precious vitamin bombs after months of bitter cold. “Some people, especially elderly people, still go out to pick these fruits. They’re the first fruits after winter: we rush to gather them before they dry out and the birds find them. Innu people do this, too. We may have learned this practice from them.”

On the North Shore, foraging is rooted in tradition. The numerous peoples who settled in this vast land over the millennia – starting with the Maritime Archaïc some 8500 years ago – have always depended on native food sources. Berries are an important part of the local pantry, including for Indigenous peoples.

Harvest activities are large family gatherings where precious knowledge is shared.

Historically, harvesting berries provided a dose of vitamin in a diet otherwise dominated by meat and fish. These fruits – as well as the leaves, flowers, and roots of their shrubs – were also used for medicinal purposes.

Berries were not the only foodstuff historically foraged here. Labrador tea leaves, for instance, were used to make herbal tea and sometimes smoked. They were also used to help wounds heal, and brewed to facilitate birthing for pregnant mothers. A pantry and a pharmacy at hand… for those who knew how and where to find it.

For Indigenous peoples, harvesting is important culturally, as well as nutritionally. Harvest activities are large family gatherings where precious knowledge is shared. Historically, this cultural transmission was damaged by the forcible settlement of Innu people. Residential schools ripped children from their traditional ways of life and from elders’ teachings. But despite decades of abuse, Innu-aitun, the Innu lifestyle and culture, lives on. Its renaissance relies on community activities, including ones where foraging takes a central place, gathering people of all ages around this ancestral practice.

For the colonizers who settled more permanently on the North Shore from the 19th century onward, wild harvesting was also an important occupation. A large array of dishes still prepared to this day attest to the prominent place berries occupy on the table: red berry steam puddings, cloudberry squares, crowberry jelly, cranberry pie, blueberry jam… A recipe for every sweet tooth.

Some of the treasures you might find

- Berries: cloudberry, cranberry, crowberry, Arctic bramble (or Arctic raspberry), highbush cranberry, red berry (or mountain berry), blueberry, raspberry

- Coastal and marine plants (be mindful of any special rules that might be in place to protect the shoreline from erosion): glasswort, wild rose, beach pea, sea lovage, many species of seaweed

- Mushrooms: chaga, lobster mushroom, yellowfoot (or funnel chanterelle), various boletus, morel, maple milky cap

- Others: dune pepper (green alder catkins), balsam fir and black spruce buds, Labrador tea, sweet gale

“Even if it’s demanding, very physical, even if the heat is crushing, even if the flies are out, we’re so thankful for everything that surrounds us, everything that lives. It inspires everything we do.”

– Annick Latreille

For the love of nature

Most harvesters collect small quantities of fruit for their personal or family needs. But over the last decade or so, a handful of small-scale entrepreneurs have leveraged ancestral know-how to turn wild foods into a livelihood. In Sept-Îles, the offerings of Trésors des Bois include daisy buds and a variety of mushrooms. In Forestville, Les Saveurs boréales harvests the famous chaga mushroom and sweet gale seeds, among others.

Professional forager Annick Latreille settled in Natashquan 15 years ago. The move was a “revelation,” according to the former literature teacher. Her small business, De baies et de sève, transforms wild treasures into delicacies: Labrador tea, fir and wintergreen herbal tea blends; balsam fir syrup to mix into cocktails; sea lovage and creeping saltbrush pesto… She sells products online and in her small boutique, which is nestled against Brasserie La Mouche. “In the summer, we’re four or five harvesters. We collect everything by hand,” she says. “We head out for five or six hours to pick one or more plants, depending on timing. Then we preserve everything right away. We never leave it to the next day. We dehydrate, vacuum seal, freeze… Most of the processing happens during the rest of the year, outside of the harvesting season.”

Annick Latreille also forages to stock her personal pantry: mushrooms, berries, seaweed to fertilize her garden, medicinal plants, black spruce buds… “Even if it’s demanding, very physical, even if the heat is crushing, even if the flies are out, we’re so thankful for everything that surrounds us, everything that lives. It inspires everything we do.”

A rich environment that nourishes both the body and the soul.

le Goût de la Côte-Nord magazine

June 2022 – Number 2

To learn more about the Côte-Nord terroir, get le Goût de la Côte-Nord magazine!